Vol. 2: The Trouble with NYT's News Analysis; Biden and Starmer's Parallel Messaging

Jack examines the pitfalls in The New York Times' apparent shift away from straight news. Mark discusses how Joe Biden and British Labour Leader Keir Starmer are offering similar pitches to voters.

Media Under the Microscope

News Analysis Is Not News. It Needs to be Published with Caution

By Jack Benjamin

Image Credit: Jakayla Toney, Unsplash

The New York Times gets a lot of flak.

As practically the only traditional newspaper of record in the US adding rather than losing subscribers and revenue, the paper attracts outsized attention for its capacity to drive media narratives and influence public conversation.

A quick glance across social media – especially if your feed is, like mine, full of journalists and political pundits – provides a non-stop drip of NYT criticism.

“Please, New York Times, stop with this ‘dueling realities’ bullshit,” wrote Mark Jacob in response to a Times article titled “Clashing Over Jan. 6, Trump and Biden Show Reality Is at Stake in 2024.”

The Times later rewrote its headline to instead say, “Trump Signals an Election Year Full of Falsehoods on Jan. 6 and Democracy.”

Jacob, the former Metro editor at the Chicago Tribune and Sunday editor of the Chicago Sun-Times, has regularly criticized the Times for its headline copy. “The Times’ timid approach to headlines is a gift to corrupt politicians,” he wrote in September.

Jay Rosen, associate professor of journalism at New York University, has also not shied away from skewering the Times. Referencing the paper’s coverage of Donald Trump’s Veterans Day speech, in which the former president invoked Nazi rhetoric by comparing his political foes to “vermin,” Rosen unfavorably compared the Times to its competitors. The Times headline read: “In Veterans Day Speech, Trump Promises to ‘Root Out’ the Left” and included details about Trump’s “vermin” comments in the second paragraph. Rosen suggested the article failed to connect the rhetoric to its fascist inspiration. Other headlines, Rosen said, such as those in The Washington Post and Forbes, avoided this mistake. In recent weeks, he has thus taken to sharing “lede workshops” aimed at pointing out the Times’ insufficient copy.

Even the Times’ own columnist Paul Krugman has gotten in on the critique. Writing about Republican presidential candidate Nikki Haley in November, Krugman said, “A recent Times profile described her as having ‘an ability to calibrate her message to the moment.’ A less euphemistic way to put this is that she seems willing to say whatever might work to her political advantage.”

Meanwhile, a fifty-two-year-old math professor going by the alias Doug J runs an Onion-like Twitter account called NYT Pitchbot. The account pokes fun at the Times’ often contrarian Opinion and News section headlines. “There’s this obsession the Times has with attacking other liberals,” he previously told the Columbia Journalism Review. There’s a reason this account isn’t called WaPo Pitchbot, or Boston Globe Pitchbot; when Americans think “mainstream media,” the first newspaper that comes to mind is The New York Times, regardless of whether comparable critiques can be made of practically any news outlet in today’s era.

With the added scrutiny that comes with its relative success, the paper is guaranteed to be displeasing to many. Criticism, reasonable or otherwise, will always outweigh praise. The world-class reporting and digestible but thorough standardized story structure at the Times deserve more credit. But the Times also needs to do a better job sorting between the many criticisms it receives and taking the most apt ones to heart.

The Times, like all other publishers, is staring down the barrel of a rapidly deteriorating digital news landscape. When consumers can get the basic news from the BBC or The Guardian or journalists posting on social media or Substack newsletters or broadcast television or TikTok influencers or Apple News or podcasts or tabloids, why would they pony up the cash for an expensive annual subscription to the Times or its many wannabes? Though the outlet has been a winner so far, the question of whether it can continue to outrun the beast of commoditization must haunt the dreams of AG Sulzberger.

Indeed, according to the latest Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism study, just one-fifth (twenty-one percent) of Americans say they paid for online news in the past year. And that is above average compared to other Western countries. In the UK, it’s a paltry nine percent.

That leaves publishers in a bind. What once was a legitimate unique selling point – exceptional, high-quality, trusted news – isn’t as valued in an age of an oversupply of free content and declining trust in news overall (just 32% of Americans say they trust news “most of the time” according to the same Reuters Institute study).

The NYT is one of the new publishers to be ahead of the curve in adapting to people’s lack of interest in paying for news. Over the past few years, leaders have invested heavily in improved Cooking, Games, and Audio verticals, which has paid major dividends. More so than in the past, subscribers now have daily reasons to make use of their subscriptions even if they aren’t keying into every day’s standard news reporting.

Lately, the paper is signaling much more drastic editorial shifts that could significantly impact its journalistic quality.

The Times now regularly offers articles tagged News Analysis and floats them to the top of its homepage, especially on days when news is slow enough that a live thread covering breaking news is unnecessary. For app users, such articles are, by default, promoted at high rates via push notifications.

These are articles like, “The Economy Looks Sunny, a Potential Gain for Biden,” “Biden’s Options Range From Unsatisfying to Risky After American Deaths,” “How Haley Lost New Hampshire: Ignoring Lessons From Underdogs of the Past,” “Is Kim Jong-un Really Planning an Attack This Time?,” and “How Biden’s Immigration Fight Threatens His Biggest Foreign Policy Win.”

Meanwhile, the paper also now has a live blog for its high-impact Opinion columnists (The Point) to allow them to react to news as it happens.

It’s not hard to point out flaws in such analysis articles’ presentation. Just from that cross-section of headlines from the past few weeks, you can see something of an overly negative sentiment expressed around Biden.

The economy doesn’t “look” sunny—it is sunny, thanks to Biden’s fiscal policy and admirable maneuvering by the Fed.

Biden’s handling of the response to American soldiers’ deaths in Jordan has been reasonable and is broadly in line with Americans’ wish to not escalate conflict in the Middle East while reacting with force to legitimate threats to American soldiers’ safety.

The “immigration fight” isn’t a fight so much as it is the GOP going back on its wish to address the border because Trump told them not to give Biden a political win in an election year.

Headlines about a potential conflict with North Korea and an article that still implies Nikki Haley has any reasonable chance in any primary contest against Trump are unnecessarily sensationalist.

And so on.

But, okay, these are analysis pieces. Like any analysis, there is room for a wide range of… opinion? But isn’t that supposed to be the realm of the Opinion section?

Any journalist worth their salt knows it is their job to report the news, not make it. “The reality is stories like this are the story,” independent journalist Judd Legum commented in reaction to a news analysis headline titled “Legal Exoneration, Political Nightmare” relating to the special counsel report on Biden’s handling of classified documents. “The NYT and other media have decided they will make this a political nightmare by endlessly publishing stories like this [about Biden’s age].”

The bleeding of opinion and analysis into news is a pitfall that broadcast channels have also fallen into over the years. News programs went from sober presenters like Edward Murrow and Walter Cronkite to pundits like Rachel Maddow, Joy Reid, and Don Lemon to attract and retain viewers in the attention economy. Suddenly news shows weren’t news unless they were in daytime hours. Rather, they were analysis and opinion programs. You don’t just want the facts, do you? You want them chewed up and digested for you. In terms of viewership figures, that appears true – after all, the likes of Maddow are ratings darlings while blander hosts like Wolf Blitzer do little to excite – but an overfocus on punditry harms trust. If Maddow is offering her opinion on news even part of the time, audiences can’t necessarily trust her with just-the-facts reporting.

This is the conundrum with having the newsroom write up analysis; it is not really news, even if reporting practices are carried over (id est, asking experts for a range of perspectives in response to a news story coming in on the wire), and it can reduce trust in reporters regardless of the high quality of their work.

Seeing as analysis articles are being offered in the Times’ news section, there is a reasonable further worry that readers will fail to adequately separate what is analysis from what is news. To be sure, it is not The New York Times’ fault that media literacy is generally in a poor state. The paper provides clear markers distinguishing “News Analysis” from standard reporting so readers can know which one they are receiving. Yet even with these markers, many readers will fail to make this distinction (especially if they are only scanning headlines), and otherwise savvy readers may still find the sudden uptick in analysis pieces alarming simply because it means the Times’ “objective” reporters are making room for, well, less just-the-facts reporting.

Throughout the history of The New York Times, and much like other reputable publishers, the Opinion section has been segmented off from the newsroom. There is no intermingling – Opinion writers find out the news at the same time everyone else does. If newsroom staff are now being asked to write analysis, they risk leaking additional bias and opinion into their work, be it their own or from experts.

The irony is this could actually be a good thing. NYT’s news stories often reek of bothsidesism due to a duty to seek out diverse perspectives in news stories, as pointed out by Jacob, Rosen, NYT Pitchbot, and more. If journalists are allowed the freedom to write “analysis,” readers could actually get something closer to the truth.

In Jon Meacham’s 2018 book, The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels, he writes of Denver Post editor and publisher Palmer Hoyt, whose response to McCarthyism is something US outlets should look to as a north star. “In a memorandum to his staff, Hoyt suggested neutrality was not the highest virtue – truth was,” Meacham describes. “Reporters should ‘apply any reasonable doubt they [might] have to the treatment of the story.’ In other words, if a McCarthy statement was demonstrably false, the journalists should feel free to say so – in print.”

You would think “News Analysis” would allow journalists to do just that, with no caveats needed. A spade can be called a spade without requiring the journalist to seek input from both the spade expert and some other loon with a large audience who doesn’t believe in spades.

And yet, because it is important to the Times’ staff and reputation that its newsroom can continue to claim objectivity, you instead get analysis articles presented with bothsidesism, awkward headlines, and the framing of standard political conundrums as existential issues for President Biden.

It is important to note just how difficult the job Times reporters have is. It is simple to criticize reporting practice when you have no idea the work behind it. It is very easy to think in conspiratorial tones (“The New York Times must want Trump elected again because it’d be good for business!”) if you lack understanding of the lengths to which reporters must go before their copy is even considered for publication anywhere, let alone somewhere with the high standards of the Times. It wasn’t until I became a journalist myself that I began to recognize how challenging it is to maintain objectivity in reporting, especially as Republicans move farther and farther to the right. The temptation towards false equivalency becomes much more empathetic when you realize calling something a “lie” typically requires some definitive evidence of intent.

Equally important to note is the quality of Times analysis. Many such articles hold real value and are appreciated by a wide subset of readers for helping them make sense of the news beyond the basic facts of a given story.

That lofty ideal of what news analysis can provide needs a stricter separation from the newsroom. If the Times wants to protect its readers’ perceptions of objectivity in reporting, the newsroom should not be in charge of analysis. Leave it to Opinion, or better yet, create a new team that solely handles analysis pieces and publishes them in a separate section.

Furthermore, the paper must maintain a greater commitment to accountability. As newsrooms have been hollowed out in recent years (weeks, even), public editors have become non-existent. The New York Times disposed of its own in 2017. “It’s about having an institution that is willing to seriously listen to criticism, willing to doubt its impulses and challenge the wisdom of the inner sanctum,” wrote Liz Spayd in her final column for the paper ahead of her redundancy. “Having the role was a sign of institutional integrity, and losing it sends an ambiguous signal: Is the leadership growing weary of such advice or simply searching for a new model?”

Public editors are indispensable in their capacity to explain coverage, refute criticism, and regularly admit to shortcomings in copy. The Times should commit to rehiring a public editor to communicate with the public more regularly when it, say, adapts a headline after publication or bleeds news analysis too far into opinion.

In an era where trust comes at a premium, The New York Times has the responsibility to lead. Regardless of the news industry’s business pressures, it must retain a commitment to quality, transparency, and reasonable objectivity in news writing. If people are willing to pay you for news, they deserve to have their conviction in your ability to tell the truth rewarded. Don’t muddy the waters. ♦

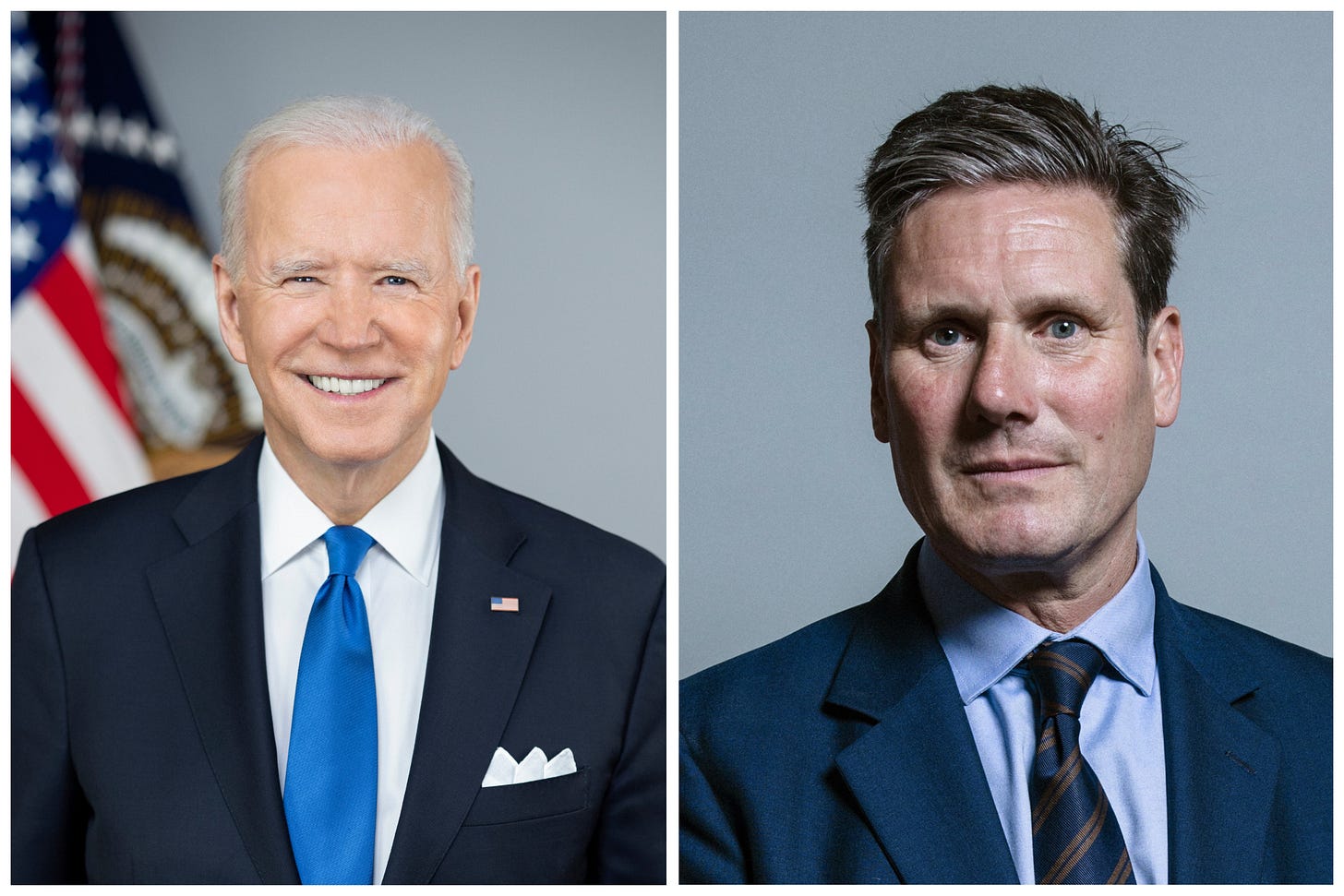

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Comms About Comms

Biden and Starmer Are Offering Their Voters A Choice Between Stability and Chaos

By Mark McKibbin

Comparing the political landscapes of American and British politics is a favored subject among scholars, journalists, bloggers, and political professionals.

Assertions that Margaret Thatcher’s election in 1979 predicted the Reagan Revolution in 1980 are commonplace. Suggesting that Clinton’s victory in 1992 inspired Tony Blair’s Third Way Politics in 1997 will spark little disagreement. Predictions that the success of Brexit in June 2016 was an ominous sign for a potential Donald Trump victory later that year abounded.

Both US and UK voters are heading to the polls this year. British Conservative Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, who can schedule elections for as late as January 2025, plans to call for elections in the "second half" of 2024 but has not provided an exact date. Opposition Leader Keir Starmer, whose Labour Party leads the Tories by double-digits in many polls, understandably wants an election sooner than that. For the same reason, Sunak has good reason to delay.

By contrast, the US elections are set for November of every even-numbered year, and the US presidential election is currently polling as a toss-up. Despite former President Donald Trump facing ninety-one felony charges in state and federal court, flirting with fascism, turning his back on NATO, and openly disdaining small-D democracy, there is a coin-flip chance of him becoming the second president in US history to serve two non-consecutive terms (the first was Grover Cleveland).

The scene from Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, where Wormtail declares that “the Dark Lord… shall rise… AGAIN!” before He Who Shall Not Be Named (Ralph Fiennes with airtight nostrils) does, in fact, rise again, aptly analogizes my waking political nightmare.

But while Biden and Starmer have different advantages (incumbency versus good polling), both seem to have presented their voters with a similar choice: stability with them or chaos with their opponent.

Starmer has underscored the Tory portrait of chaos through a laundry list of scandals, such as “sex scandals, expenses scandals, waste scandals, contracts for friends," and the mismanagement of the pandemic. Biden has presented voters with a similar image: “Just think back to the mess Donald Trump left this country in,” he said on January 29. “A deadly pandemic, economic freefall, a violent insurrection.” Both have zeroed in on the chaos their opponents fomented in office. Both hope that their victories will not only mark the defeat of their immediate opponents but also an end to their opponents’ way of doing politics.

Both also have political baggage. Searches for “Keir Starmer charisma problem” and “Joe Biden age problem” yield no shortage of results, thanks in large part to American and British news outlets ridiculously equating these subjective labels with the far more egregious crimes and ethical lapses of Trump and the Tories. Recent coverage from CNN and The Economist provide apt examples of this bothsidesism—both outlets love drawing false equivalencies between the two major parties in their respective countries almost as much as I love watching Ice-T serve up clever comebacks to shady characters on Law & Order: Special Victims Unit.

But neither Biden nor Starmer need to become a rockstar or (in Biden’s case) unearth an anti-aging elixir to secure victory. Biden is not Barack Obama. Starmer is not Tony Blair. Voters do not expect them to be. Instead, Biden and Starmer are rightly betting that if they can convince voters of their competence and present a stable antidote to the pandemonium of their opponents, that will be enough to win.

For this reason, Biden and Starmer are heavily leaning into messaging that emphasizes a return to or restoration of norms their opponents have compromised. Biden’s website features a campaign ad highlighting his fight to restore “the soul of America,” just like when he ran against Trump four years ago. Biden’s speeches foreground his commitment to protecting the Affordable Care Act and restoring the legality of abortion nationwide.

Most planks on the Labour Party’s website center around a promise to return Britain to the stability of the past: getting Britain building again, switching on clean British energy, cracking down on violent crime, and getting the NHS back on its feet.

Such messages are, ironically enough, fundamentally conservative in nature. They are about a return to the (recent) past when things were regular and not panic-inducing. If the 2024 US and British elections were a dinner menu, the two à la carte menu choices Biden and Starmer would be offering voters would not be right-wing versus left-wing soup surprise. It would be crazy pills versus meat and potatoes.

Biden and Starmer focus on these issues because they understand that voters, who may not have a high affinity for either candidate in a vacuum, will view them more favorably when they associate them with steady leadership and solutions-based politics.

Will such a messaging strategy work? There is more certainty for Starmer than Biden because, in the US, comparatively more political unknowns remain. Will Donald Trump be convicted of crime(s)? Will voters start to give Biden more credit for the economy? To what degree will Nikki Haley voters fall in line behind Trump?

I will not try to answer these questions. As a general practice, we at the Thornfield Quill are consciously trying to avoid the kind of armchair quarterbacking and horse-race punditry that may get Chris Cillizza a lot of clicks but generally hinders rather than helps America’s political discourse.

It is more appropriate to use the clues Biden and Starmer have already given us to analyze why the two believe they have a good hand to play in 2024.

Neither Biden nor Starmer are betting they can outdo Donald Trump or Nigel Farage in the art of performance. Instead, they are making another bet. Each has staked their political fortunes on the gamble that voters will opt for boring competence over political theater and a future with fewer, rather than more, heart-quickening alerts popping up on their phones.

By this time next year, we will know if that bet paid off. Even if it does, whether a re-elected President Joe Biden and new Prime Minister Keir Starmer can translate their wins into sustainable political power when their parties face voters again later this decade will remain an open question. ♦