Vol. 15: Erik Larson Book Review, Confessions of a Eurovision Convert

Mark reviews Erik Larson's new Civil War-era book 'The Demon of Unrest'; Jack discusses why he's developed a soft spot for Eurovision and its cultural and political importance.

Review

The Problem of Leapfrogging in The Demon of Unrest

By Mark McKibbin

If Erik Larson’s new book, The Demon of Unrest, had been three, four, or five different books, and I had read any of them, I would probably be writing a glowing review. But as a single volume, Larson’s masterful writing style and potent sketches of individual historical figures were eclipsed by his narrative leapfrogging.

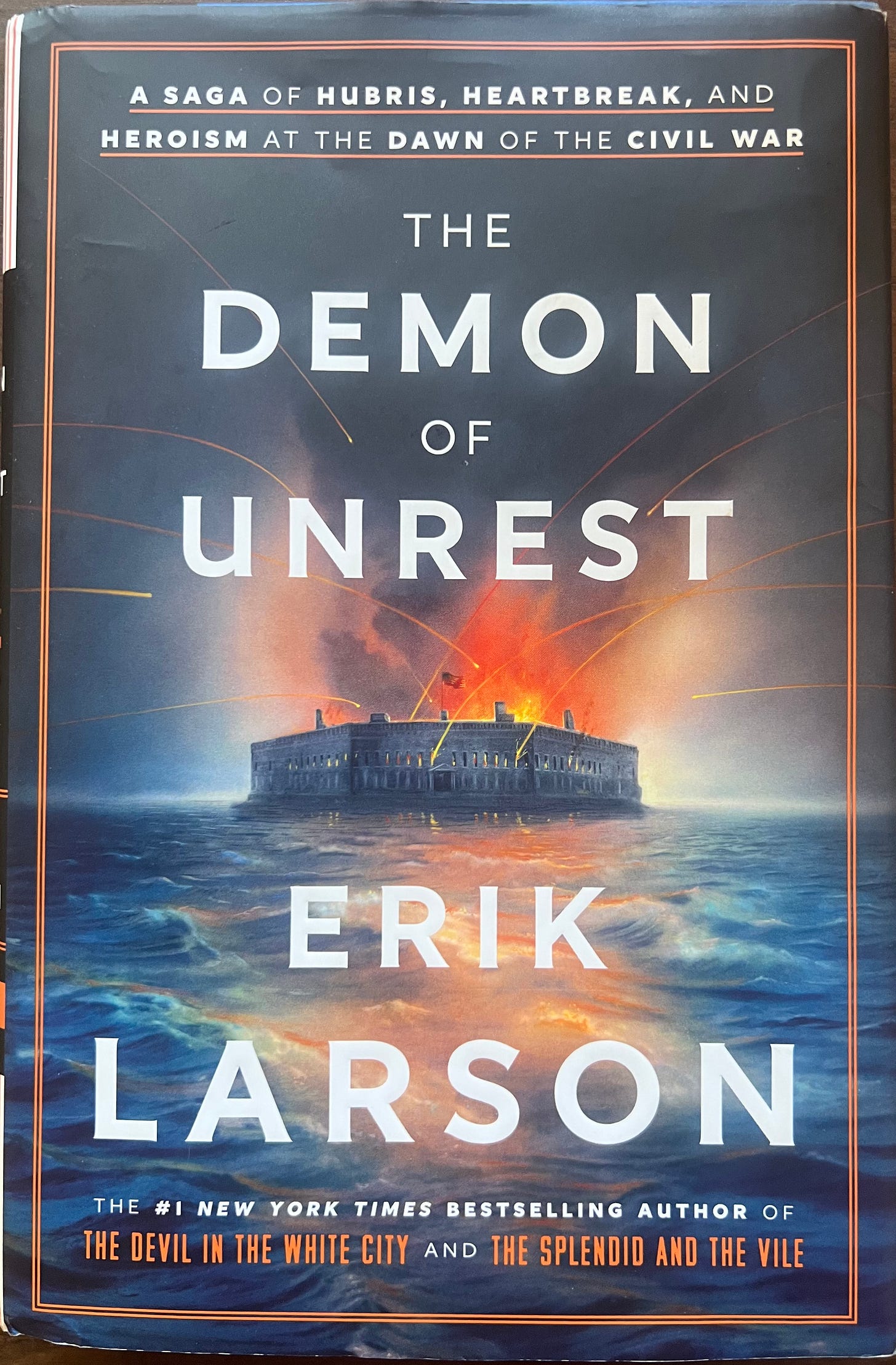

The Demon of Unrest covers the period between November 1860 and April 1861, beginning with Abraham Lincoln’s election as the 16th President of the United States and ending with the Confederate shelling of Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. In between, Larson provides snapshots of the major figures relevant to the months leading up to secession, including Lincoln, Lincoln’s predecessor James Buchanan; Major Robert Anderson, who led the Union’s defense of Fort Sumter, Virginia secessionist Edmund Ruffin; and South Carolina secessionist (and rapist) James Hammond. We witness the various southern states hold conventions that vote by wide margins to leave the Union. Larson attempts to make readers feel as if they are “in the moment” in the events he describes, understanding the suspense that the book’s subjects must have felt about the impending secession crisis.

My main quibble with Larson’s book is that he tried to do too much. I felt like I had been oversaturated with narrative detail but left wanting on interpretive historical detail. Consequently, I failed to meaningfully connect with any of Larson’s subjects, whether they be his heroes, his villains, or his heartbreakers.

Perhaps most importantly, given that Fort Sumter was pictured on the cover of the book (in this way, I am judging the book by its cover), I failed to walk away from this book with a concrete sense of the “so what?” about the skirmish at Fort Sumter that led to the “first shot” of the Civil War. Why did the skirmish at Sumter matter? What did it signify about the state of the nation? How did it embody the nature and tenor of the time?

In multiple instances, I can point to isolated parts of Larson’s book I really enjoyed. The stirring ways Larson ended his chapters blew me away. I appreciated the invigorating portrait Larson paints of the chivalry that pervaded South Carolina’s culture, weaving a potent narrative about how South Carolina sought to mix chivalry with ferocity in the months leading up to the Civil War. As I was reading the book, I could not help but notice the parallels between Larson’s narrative and Margaret Mitchell's discussion of chivalry in Gone with the Wind.

Larson’s narrative aptly connects how the South’s obsession with chivalry fueled its obsession with defending slavery. To defend their “utopian” way of life sustained by the dystopian existence of the enslaved, white southerners portrayed slavery as a social as well as an economic good for American society. I was glad to see that Larson left no doubt to readers that slavery, not “states’ rights” or “Northern aggression” or any of the other bullshit Lost Cause narratives that Nikki Haley picks from her grab-bag of town hall talking points, was the cause of the Civil War.

Some reviewers have criticized Larson’s portrayal of slavery as an overly sanitized portrait of the depraved existence to which southern whites subjected enslaved blacks.

As a rule of thumb, I am highly sympathetic to any criticism that a writer has minimized the horrors of slavery. I am also sympathetic to the reality that words on a page will never be able to fully encapsulate the barbarity of the American slaveholding system. I agree that Larson could have paid more attention to the plight of enslaved individuals and described it in starker terms. With that said, I give Larson credit for making a good-faith attempt to underscore the horrors of slavery, particularly in the places where Larson cited primary source accounts of the grotesque sexual violence committed against enslaved women.

I try to judge books for what they are rather than what they are not. The history books I generally read are heavy on analysis. Larson's book was intentionally more driven by narrative, so I was not expecting a complex and striking academic analysis of historical events.

However, I do feel warranted faulting Larson for being so focused on the narrative that his portraits of individual people and events felt like hit-and-run descriptions rather than detailed portraits like the kind that made Larson's The Splendid and The Vile, which focuses on Winston Churchill's leadership during the German bombing campaign against Great Britain in World War II, so compelling.

Larson began The Demon of Unrest by discussing South Carolina and Fort Sumter. Then he started jumping back and forth between the North, South, and West. He leapt between Springfield, Illinois, where Abraham Lincoln finds out he has won the Election of 1860; Washington, D.C., with a vacillating President James Buchanan showing pitiful cowardice in responding to secession; and Charleston, with various secessionists being predictably racist and inhumane while plotting the demise of the Union. Then he went back to Lincoln. Then back to Buchanan. Then back to Charleston. Larson’s chapters went on like this for the next several hundred pages, with several more cities and characters being added on. It was fatiguing.

As a narrative technique, leapfrogging can be effective—it worked marvelously for Anthony Doerr in All the Light We Cannot See and Doris Kearns Goodwin in Leadership in Turbulent Times, for example. However, for a nonfiction book on a topic as discussed and complex as the first months of the Civil War, the leapfrogging approach was misplaced.

Reviews of The Demon of Unrest have noted that when Larson finally got to the details of the attack on Fort Sumter, it felt sluggish. I would agree with this assessment. I would also suggest that Larson’s abrupt switch from leapfrogging across the country to focusing on an isolated place felt sluggish precisely because Larson’s leapfrogging in the first three hundred pages of the book had not prepared readers for sustained focus on one place.

Perhaps most egregiously, Larson’s tendency to leapfrog led him to echo tropes of historical analysis that most contemporary historians have come to reject. For example, Larson parrots the tired and idiotic assertion that Robert E. Lee “hated” slavery and only sided with the South because of his loyalty to Virginia. Even as Larson made the Confederacy the villain of his story, he nevertheless painted a more sympathetic portrait of the Confederacy than the Confederacy deserves.

If Larson had focused on fewer regions of the country or found a better way to go between those regions, perhaps he could have avoided the pitfalls that plagued The Demon of Unrest. If Larson had limited himself to one, two, or even three major subjects rather than the merry-go-round of figures we got, his narrative might have been more gripping. As a critic, it is not my role to pinpoint what the “right” choice would have been. Rather, it is to examine the choices the creator did make and assess whether those choices helped or hindered the creator’s objective for their work.

In his preface, Larson expressed his desire that readers would feel a “sense of dread” as they read his account.

I certainly had a sense of dread while reading The Demon of Unrest. But it came less from the described events than my dread that behind every beautifully crafted chapter ending lay a discombobulating change in setting. So, in a way, Larson succeeded, but not in the way I suspect he intended. ◆

Lost in Translation

Confessions of a Eurovision Convert

By Jack Carter Benjamin

To be an American in Europe on Eurovision weekend is to be a stranger in a strange land.

For those of you across the pond unaware, the Eurovision Song Contest just wrapped its sixty-eighth competition. A post-war broadcast staple within Europe, it brings together (usually) not-yet-discovered musical artists from across European countries to compete to see who can perform the best under-three-minute song. Delegates from each country then award points to their favorite performers (known as the jury vote), and viewing publics vote as well to decide the winner.

Imagine if American Idol was still popular, and also its contestants did a lot of cocaine. That’s Eurovision. It’s camp. It’s kitsch. It’s a big hit with the LGBTQ+ community. Oh, and fifty years ago it introduced us ABBA and thirty-six years ago, Celine Dion, in case you weren’t aware.

It is obviously unfair to stereotype the people of an entire continent. And yet, is there anything more stereotypically “European” than Eurovision?

My first time watching the broadcast was in 2021 when I was a graduate student at Oxford. After receiving incredulous looks from my European peers when they found out I’d never heard of Eurovision (“Come può essere possibile?”), I joined a watch party and found the experience, in a word, hilarious. The performances were completely over the top but delivered without a shred of irony. It won me over. I felt nothing but appreciation for the event. Italy’s Måneskin took home the top prize, and you know what, they actually totally rocked.

After watching in 2022 (highlighted by the U.K.’s Sam Ryder) and 2023, I was by then a full-on convert. It’s goofy, it’s European, but damn it, it is good fun. And (sans Ryder) it is always hilarious to see how poorly the U.K. performs post-Brexit. Rooting for the U.K. is akin to rooting for the Cubs. They’re losers, but they’re loveable losers, especially with Graham Norton offering tongue-in-cheek commentary throughout the evening’s festivities.

In general, the music is – if I’m being absolutely honest – poor quality to the point of being offensive. Most songs are pop drivel, with a mix of melodramatic ballads (often featuring a large amount of what can only be described as wailing) sprinkled in throughout the night. Every so often you’ll see a song deeply rooted in a country’s musical culture (for example, this year’s entrant from Armenia), which at least win my brownie points for offering something unique. But it is rare to find artists performing here that are genuinely good, let alone ground-breaking. If you want music excellence, avert ye eyes.

Performances are also often highly sexualized (I can hear those American pearls being clutched from three-thousand miles away). To borrow from Game of Thrones, “A Eurovision song contest without at least two-dozen shirtless male dancers is considered a dull affair.”

This year’s (and last year’s) most ridiculous performance surely goes to Finland, if you’d like a taste for how outrageous things can get.

While the niche cultural importance of Eurovision is obvious in its ability to highlight new musical acts to a wide audience (regardless of their artistic quality), its political benefits should not be understated. Like the Olympics, Eurovision offers an opportunity to express unity between countries that, with little exception, have spent centuries at war with one another. It is an important part of creating a unified European identity, even as the continent struggles to remain on the same page in international affairs, despite intertwined economic ties.

The spirit of Eurovision is intended to be apolitical. Any lyrics deemed to be too political, for instance, are required to be changed. This was true in the case of this year’s contestant from Israel, Eden Golan. Golan’s song, originally dubbed “October Rain” in likely a reference to the October 7 Hamas attacks on Israel, was changed to “Hurricane” to remain eligible for the contest.

But politics do play a part in the festivities. This year’s Eurovision, held in Malmö, Sweden, was heavily protested by pro-Palestinian advocates (including Greta Thunberg). And in prior years, the contest has been used to show solidarity for countries affected by war, such as Ukraine in 2022 (Russia was banned from performing), and has been impacted by regional politics, like in the case of Armenia and Azerbaijan.

The tensions this year were predictable. While Israel is not in Europe, countries outside the continent are able to enter so long as they pay the European Broadcasting Union (EBU) a participation fee and fulfil other entrance conditions. Australia is the only other current non-European country that regularly competes.

Given Israel’s apparent global unpopularity amid its attacks on Gaza in response to October 7, protests were expected. While Golan performed admirably, any points issued to Israel were met with a chorus of boos from the live audience, as was the EBU’s Executive Supervisor Martin Österdahl. The event this year was not without additional controversy – the Netherlands’ contestant Joost Klein, who had been openly disparaging of Israel, was kicked out of the competition the day of the final due to allegations of misconduct reported by production staff.

Anti-Israel sentiment was high amongst other contestants as well. Irish contestant Bambie Thug donned a keffiyeh scarf and told press they cried when they found out Israel had made it to the final round.

It was an important show of political unity, then, that despite the boos, the protests, and general purported anti-Israel sentiment in Europe, when it came time for the public vote to be counted, Israel received the most points from fourteen of the thirty-seven eligible voting countries, and the second-most points from an additional seven (including Ireland). In total, Israel placed fifth overall (out of twenty five), with Switzerland’s Nemo taking home the top prize thanks to high marks from the jury vote.

Should a relatively frivolous public vote for a song contest be used as a gauge for public opinion toward Israel? No, not really. It should be noted the competition’s ratings dropped in the U.K. due in part to a planned boycott. Still, this year’s Eurovision offered a stark reminder of the power of silent majorities.

Oh, and it was yet again a great time, even if it need not take four hours to conclude.

Next year, if you’re an American, you should consider watching. If not for the underwhelming music, then at least to check the pulse of the European sensibility.

(And to see whatever it is they’re smoking in Finland.) ◆